Data Siphons

Part 2: How content creators lose out on the value of their data?

In the previous installment of this series, I wrote about demonetization. The take-away message is that a great deal of monetization happens away from the content. If you haven't yet, I suggest you read that piece to learn how to improve monetization.

This article will discuss how content platforms leak data without monetizing it, which gets monetized by others. Data siphons are how data gets lost. In the end, you'll better understand how the power and revenue have shifted away from content and what we can do about it.

"Data is the new oil" has long been a rallying cry of entrepreneurs and consultants. In the beginning, data flows were virtually free. Data sources were tapped, information was extracted, leveraged for various purposes, or sold to hedge funds. Data tappers grew rich, even if few of them owned data directly. Many data owners were all too eager to outsource their data, so data access was cheap.

Many have been giving away their data rights for a pittance. The success of data tapping might have awakened some of them. Most, however, are still unaware of how and what data continues to be siphoned away. As a data science researcher, I'd like the data to serve those who create content, not against them. Internet depends on quality content, so the future of the internet depends on how it will treat the creators and curators of content and data.

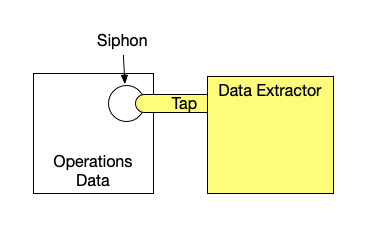

Let's define it: a data siphon is where data extractors tap into someone else's data. Here’s a sketch:

The goal for a wise data operator is to control the siphons. The trouble is that very few content platforms prevent siphons, and even fewer support siphon control. Increasingly, the owner of the data stores all of it inside a 3rd party SaaS platform (content management system, social network) and trusts it not to abuse the data but has no direct way to protect the data. The owner that depends on platforms can lose access to his data. 3rd party analytics systems discard data as a standard practice: I learned this the hard way doing deep data analysis for a popular internet service that relied on Google Analytics.

In the coming years, you'll be hearing more about data siphons and secure data platforms. As time goes on, we need to shift to a world where it's theoretically much harder to tap someone else's data, and we don't just rely on trusting our vendors. In the meantime, however, let's explore the kinds of valuable data content generates. Here's a categorization with more information:

Audience Data: Knowing your audience and contacting them is best understood of all forms of data. Social networks promised you to grow your audience by giving the social network platform control of it. This pyramid scheme did reward a few early adopters. Still, as with multi-level marketing schemes, the late-comers ended up donating their network to the platform. The platform and those tapping it can extract the audience and use this for other purposes, including launching competing content. This data is typically non-problematic: media of the past knew who their subscribers are, and newsstands knew who bought what.

Engagement Data: Knowing what part of your content is getting read, copied, shared, engaged with is incredibly valuable to developing better content. A mere fraction of the available data is shared with the creators. This data is non-personal and analyzed in aggregate form, therefore rather non-problematic. The cookies used for this purpose serve merely to avoid double-counting a single user through multiple page loads. However, it had been costly in the pre-interactive era (Nielsen is a multi-billion business). Now, it's virtually free if your platform shares this with you, of course.

Interest Data: This is where the privacy issue starts appearing: deeper analytics can help establish who is interested in what. Interest data is sensitive for two reasons: few people are trusting enough to let someone else monitor what they're reading - and only massive data operations can do anything useful with such data. Some publishers experimented with automatic recommendation systems, but there have been relatively few success stories that didn't leverage massive data. However, in practice, interest data facilitates profiling: knowing what a user is interested in allows advertisers (including other publishers) to target them anywhere else.

Content is data: Copyright seeks to protect investment into content, but rules and legal practices date back to armed disputes in the era of scribes. The most important use case, however, is re-curation. Re-curators are non-creators who can develop their own audience, create their own monetization, shape their own editorial voice, and even build their own interest data simply by sharing links to free content. Search engines and social networks are the ultimate re-curators who have begun to even re-curate the re-curators through algorithmic feeds.

There have been some legislative initiatives to prevent re-curation by banning deep links. Of course, by now, an AI can devour an article and regurgitate a new deep-faked piece of content containing the same information without breaking any (current) laws. Even a decade ago, content farms were siphoning off original reporting and thinking, but by now, the situation has deteriorated dramatically. The lobbying efforts are typically disguised as attempts to improve access to knowledge. They do this by empowering platforms and re-curators at the expense of people and organizations that create and curate this knowledge. In the end, there's less knowledge for everyone, and the quality is worse, but the platforms get entrenched and all-powerful.

What should we do? There are some simple lessons for a content creators/curator:

Scrutinize the platform's business model and terms of service

Seek to own your platform and your data

Be aware of siphons: plug them or meter them

Advocate a broad rethinking of how society should protect investment in content

You might be wondering how simple it is to plug the siphons. Regardless of how secure internal IT might be, most tapping happens through abundant siphons on the customer side. Those are incredibly hard to control: the internet's general architecture has not been designed to prevent siphons, and taps can be set up in numerous ways:

Cookies can be dropped by 3rd party advertising. Browser companies have almost entirely plugged this siphon. On the other hand, this and consumer privacy regulations have mainly served to entrench the data tapping oligopoly held by the most powerful internet companies over smaller advertising networks.

JavaScript code, typically web analytics plus SSO login, payments, and social sharing, can engage in almost arbitrary telemetry on the web pages loading them. JavaScript is a widely unappreciated source of siphons, even if telemetry can be detected in theory.

The web serving platform has undetectable access to almost everything, and an audit is typically impossible.

The internet browser can see everything that the customer is viewing and transmit this information virtually undetectably.

The operating system, privileged applications, or security holes of the user device can monitor anything on the device virtually undetectably.

Network operators, router manufacturers, and virtual private network software typically cannot see the content of communications but can see what websites and apps users are accessing.

The hardware manufacturer can intentionally or unintentionally facilitate data taps for sophisticated operators.

To summarize, creators and users are forced to trust numerous vendors, and the regulators are trailing general data tapping practices by approximately two decades. It's an incendiary setup, and the best way to tackle it is at the systemic level through the digital equivalent of fire code regulations, which I've written about in a contribution for a European Parliament group.

In the future, data will become as expensive as oil, and digital power will be rebalanced. But the first step to take would be to limit the use of dark data - procured through opaque means and unlicensed siphons. For example, I might now have access to what are my Google or Facebook profiles. I still don't know precisely how they established those profiles and exactly what data they're keeping (or can generate) on me.

Generation of personal data is an important consideration, as the tech giants have been shifting from keeping data on individuals to instead keeping data on "cohorts." Cohorts are no assurance of privacy, as cohort data can postulate personal characteristics with high accuracy.

In the following installments of this series, I will cover at least two more weaknesses of publishers' currently available revenue models, proceeding to upcoming changes and opportunities. Subscribe to be notified of posts as they get published! And join the conversation by posting a comment.

Thanks to Ash Kalb for comments that improved this article!

👏👏👏